Our new deacon was introduced during Mass this Sunday and he gave his first sermon.

“[The local warehouse store] is filled with SUVs,” he stated, “and people are looking for bargains. And then there is 7-11, where poor people have to shop and pay a premium for what they buy.

“Southland Corporation and Halliburton make profits,” he continued. “Illegal aliens cross our border from Mexico, trying to grab the umbilical cord here and make a better life for themselves. A scared, young soldier [because, of course, old soldiers are never scared—ed.] is in Iraq, wondering how he found himself there because the recruiter said, ‘Be all you can be.’

“Can I have an ‘Amen!’” our new deacon said to the congregation who drives SUVs to the local warehouse store, who work for corporations that make profits, and who have sons and daughters working in Iraq.

He had to ask twice before he got a very, very weak “Amen.”

“Why are profits so terrible?” I wanted to ask him.

I have personal experience with the importance of profits. Because of lack of profits, I have had my wages frozen—with three different companies, two fairly large and one a small, family-owned operation. I have been laid off twice because of lack of profits. I have witnessed two companies declare bankruptcy—one came out of it, the other did not. If a particular store does not make money, the company closes it. Sometimes that will be merely an inconvenience, such as when the local chain store (and informal community center) in my town recently closed. Sometimes, however, the store is the only place to buy milk, bread, diapers, and a cup of coffee on the way to work. It may be the only place open at 11:00 p.m. when the baby is crying because of a fever and you need liquid Tylenol. Or formula.

Southland Corporation has to pay its employees. They have to pay for electricity and natural gas. They have to pay for insurance to cover their losses due to shoplifting and to robberies. They have more storefronts than the average warehouse store (which, because of its size, tends to be in a remote area), and so higher leasing costs. These costs are reflected in their prices.

And investors in Southland, which include pension funds as well as private citizens, expect to have a return on their investment as well.

Our deacon has an “outside” job. He works for the County. So his experience with profit may be a bit different than mine.

“What is Mexico doing to make life better for their citizens?” I wanted to ask. According to the CIA World Fact Book, Mexico is rich in the following natural resources: petroleum, silver, copper, gold, lead, zinc, natural gas, timber. They are lacking the infrastructure needed to take advantage of these resources. But is that the fault of the United States? Corruption, usually in the form of bribery, is systemic and widely acknowledged.

Over $16 billion is sent to Mexico from immigrants, legal and illegal, living in the U.S. This is Mexico’s second leading source of foreign exchange, after petroleum. Most of that is spent on basic necessities by the families in Mexico, not saved nor invested. That’s also $16 billion not invested in the U.S.

Once again, we come back to that nasty word: profits. Without profits, companies—or countries—can’t save, can’t invest in the infrastructure necessary to modernize, to increase production, to make goods and services cheaper and more affordable. When the leaders are skimming the profits, the situation becomes very grave. It is convenient to have a scapegoat, a neighbor that will never miss whatever it is you are stealing from him: jobs, cash, quality of life.

Illegal immigrants do not do the jobs Americans won’t do. Illegal immigrants do them cheaper than legal immigrants. (I don’t understand why ethnic organizations, ostensibly concerned with the welfare of their members, aren’t doing more to restrict illegal immigration.) I washed dishes in my college dormitory because it paid more per hour than working check-in at the door. My dishwashing job also brought home the fact that for some of the permanent employees, washing dishes was their livelihood, not merely a way to earn pocket money.

So what does all this have to do with getting my nails done?

I have had, maybe, three professional manicures in my life. I know many women who “get their nails done” almost religiously every two weeks. I always thought it was kind of silly—after all, my fingers are typing or plunged into dishwater or chopping vegetables or cutting meat or scraping something gross out of a drain. Why would I spend good money on something that I was going to ruin in a day or two?

My outlook changed, though, when a friend of mine started to get her nails done regularly.

She and I are a lot alike (according to our husbands). We camp, we hike, we play guitar, and we work on computers most of the day. We haul gear and food in and out of our cars with the guys. Our hairstyles and our makeup—when we wear it—are simple.

A couple of summers ago, she and her daughter (who is a year older than DD#2) went out and had their nails done. It was a spur-of-the moment decision, made, in part, because “the boys” were at Scout camp and getting your nails done was such a girly thing to do. They enjoyed it so much that they continued. Every two weeks, they have a mother-daughter date at the manicurist.

I thought, “What a neat thing to do.” And I’ve begun to look for mother-daughter activities that are special. Because of school policy, DD#2 can’t wear nail polish. So our activities usually center on shopping at different craft stores for whatever projects have caught our fancies.

My feelings about manicures—and about profits and illegal immigrants—changed when my perception of their purpose changed. Profits are not “evil” when I realized my paycheck was tied to them. Illegal immigrants are as much a result of the decisions and governing practices of the Mexican government as of the decisions of the U.S. And manicures are as much about bonding as they are about vanity.

Our new deacon and I have differing perceptions of the purpose of at least two of those. Will I have the chance to discuss those differences with him? Will those differences come between us, preventing me from hearing what he has to say and vice versa?

I’ll let you know after his next homily!

Monday, March 20, 2006

7-11, Illegal Immigrants, and Manicures

Posted by

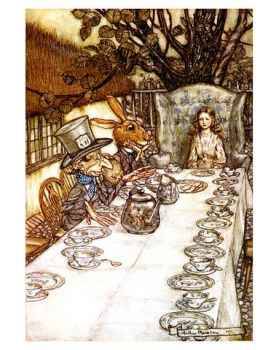

March Hare

at

2:19 PM

![]()

Subscribe to:

Comment Feed (RSS)

|