The authors, Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus, have taken their years of experience working as nannies for some of Manhattan's upper class families and turned them into a novel that is funny, frustrating, and, ultimately, sad.

They are not kind to their former employers, skewering their obsessions with overprogramming their offspring to give said children an "edge" to get into the right preschool, the right grammar school, the right prep school, leading to the right university. Every minute of their children's lives is scheduled and manipulated, their diet monitored, their playdates arranged with an eye to all important social connections.

Nanny is a senior at NYU, studying child development. She has worked as a babysitter, and later as a nanny, since she was 13. She has the drill down cold. She also has divided the mothers into "types." Type A needs a nanny to provide "couple time" for people who work all day and parent the rest of the time. This type of mother will treat the nanny as a professional and with respect. Type B requires "sanity time" a few afternoons a week for a woman who is basically an "at home" mom. She recognizes the childcare as a job and after one "get acquainted" afternoon, leaves her children with the nanny and lets the nanny do her job. For Type C, "I'm brought in as one of a cast of many to collectively provide twenty-four/seven 'me time' to a woman who neither works nor mothers. And her days remain a mystery to us all."

Of course, the mother in The Nanny Diaries is Type C, with a high level, high powered investment banking husband who cannot remember Nanny's name. Neither parent acknowledges that Nanny might have a life outside of their apartment, although Nanny shares a studio with a friend and has given them her class schedule.

The child is named Grayer, and he is all but invisible to his parents, brought out for special occasions, displayed, then returned to Nanny's care.

Nanny's first challenge is to gain Grayer's trust. He is four and loves his previous caregiver who has been dismissed for having the audacity of requesting a week off in August. Nanny is not sure how to handle this until her dad advises her to be Glinda, the Good Witch, when Grayer is behaving, but to switch into Bad Witch mode when he is not. It works, and Nanny is swept into the whirlwind that is Grayer's life.

It doesn't take long before Grayer's mother, Mrs. X, begins to ask Nanny to do a "few errands" outside the scope of childcare. Nanny's own mother, her grandmother, and her father sound like a Greek chorus, urging Nanny to stand up to Mrs. X's demands, which are not truly outrageous, but are insidious.

To top it all off, Nanny meets someone, nicknamed "Harvard Hunk" (or H. H.) in the elevator of the apartment building. There may be chemistry between them--if they could only meet when she doesn't have Grayer by the hand or he's not leaving for school or vacation or an internship in a foreign country.

Then Nanny finds out that Mr. X is having an affair with the head of the Chicago office. Ms. Chicago sees herself as the next Mrs. X and is willing to use Nanny to force the situation. While Nanny doesn't care about Mr. X or Mrs. X, she does care about Grayer. And Grayer desperately wants the attention of his parents.

The situation comes to head at Nanny's graduation. And the resolution is true to what we've seen of the characters involved.

Along the way we meet other nannies, other household help, consultants, and parents who live in this insular world. Mrs. X doesn't quite know what to do when she meets parents who actually eat dinner with their children. Other parents seem quite willing to foist their offspring off on Nanny while they are visiting, even though they have never met her before. The adults and their children are lonely and lost. Nanny's family, on the other hand, are emotionally close. They might not like what their daughter and granddaughter is doing for a living, but it's concern borne out of love, not control.

This book is kind of like watching a train wreck. You know it's coming, you know the ending can't be any good, but you can't stop. I only wish that the parents portrayed in this book read it and recognize themselves (and save their children expensive therapy), but I don't think they will. Reflection is not something that is done.

The rest of us can shake our heads and maybe feel a bit better that not getting into Harvard might not be fatal.

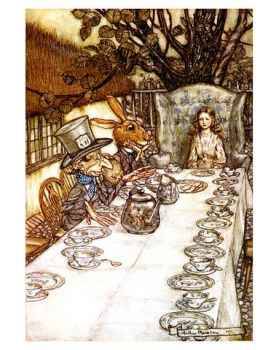

On the March Hare scale: 3.5 out of 5 Golden bookmarks

Thursday, November 23, 2006

Book Review: The Nanny Diaries

Posted by

March Hare

at

3:00 PM

![]()

Labels: Book Reviews

Subscribe to:

Comment Feed (RSS)

|